You have a music background, right? When did your engagement with music begin?

I was fortunate to grow up in an environment surrounded by music. My mother had a vast record collection, my favorite of which was an album of Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos – I loved the blasting of the baroque horns through the stereo.

But in terms of making music, that really began in the fourth grade – the year I started playing trombone and singing in the school chorus and the year my grandparents first brought me to a concert by our local symphony orchestra (The Syracuse Symphony). I was immediately enamored with the soundscape of the live orchestra and the energy of the conductor. From then I was asking for CDs of Beethoven and Mahler (while my friends wanted CDs of Eminem and Britney Spears).

Of course, I was also fortunate to have amazing music educators who fostered my relationship with the arts.

So there really wasn’t a singular experience that sparked my relationship with music, I was blessed with an environment that fostered those early experiences.

You grew up surrounded by opportunities to study and perform. How did that connect to your later experiences?

By the time I graduated high school, I understood that participation in the arts was a collective activity. I was fully aware of the ability for these opportunities to bring people together. I realized that shared experiences build community. That was powerful for a young person, shifting my understanding of that cliché on how music transforms the world. Well, the pitches and rhythm don’t actually change the world, it’s the ability of music and musical experiences to bring people together, unifying diverse individuals and perspectives into a single experience that helps change the world. That’s powerful and that’s what’s driven me since.

After high school you then went to college – how did those experiences change your understanding of the ability of music to bring people together?

My time at Westminster Choir College provided me with the framework for better understanding the ways that music brings people together. While there I had amazing opportunities – recording Grammy nominated albums, performing in the Spoleto Festival every May, singing with Celine Dion and Andrea Bocelli in Central Park, and performing with the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, and Philadelphia’s Kimmel Center.

But it was the work with my education professors – one, in particular – that gave me the language and a critical understanding of society, economic and symbolic capital, and education. I specifically remember sitting on stage at Carnegie Hall during a performance with Gustavo Dudamel and I stared out at the audience, who were all dressed in tuxedos and had probably gone to fancy dinners before paying several hundred dollars per ticket. It occurred to me that there’s more to music than this elite, gilded hall. That’s when I really became animated about teaching.

After graduating from college, you taught for two years as the choir director at Grafton High School in York County. How was that experience for you?

When I began teaching it was important to me to not only emphasize the technical aspects of music-making, but also the emotional, the ways in which making music together could transform perspectives and inform experiences. That transformation goes both ways – for the teacher, as well. I was fortunate to have a group of African American male students who transformed my views of the social role of education.

They’re the ones who really got me looking at the connection between education and society. They were the ones who opened my eyes about the systemic disadvantages that come with being a member of a marginalized community.

I’m forever grateful to them for being open and honest with me about their experiences because it really solidified the importance of education in society. So, it’s kind of been like a triangle for me, trying to incorporate the arts, education, society and how those pieces fit together and the power therein of when they do fit together.

You say that your “whole focus changed” after you left York County and went to Germany to further your studies and see more of the world. Why is that? (Drew received a master’s degree in conducting from the Hanns Eisler Hochschule für Musik in Berlin.)

In Germany, they emphasize music as something very sacred; it’s quasi-religious. So, the expectation is that we are there to serve the music as though it were a deity itself, and I fundamentally disagree with that. I think that music and the arts are there to serve us and they’re a means of connecting with real living human beings today, and so my time in Germany was a transitional period. I came back to the United States with this renewed purpose but also wanting to ask more questions and deeper questions.

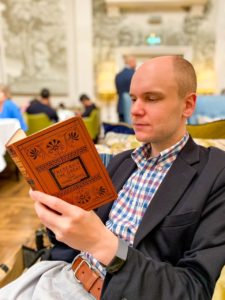

I can pinpoint the exact weekend when I decided to give up any dream of being a conductor or a fully devoted professional musician. I was invited to conduct in the south of Germany, in a town called Marktoberdorf – famous for its choir competition. I was staying in this old monastery that has been converted to a music center and there was this choir from Argentina that I was conducting. It was a great experience, but I brought with me a book by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, and I was just so enraptured by his ideas on knowledge and society that I realized, as I was sitting in this modernized monastic cell, that my heart was in a different place.

I just wanted to sit and read and enjoy the sunshine coming into my window. It was springtime and I could smell the freshness of the earth outside and I was more focused on that and the ideas of the book than on actually conducting the ensemble.

I just knew that I was closing a door and I was doing that intentionally, shifting to something else.

Is that when you returned to Virginia?

Yes, I finished my master’s degree and the work that I was involved with in Germany before returning to Virginia. I became the vocal music teacher at Old Donation School in Virginia Beach and enrolled in a master’s degree program at UVA, studying Educational Psychology. The work I was doing in the classroom reflected the themes I was exploring in my studies.

At this time I also became a researcher for the university’s Institute of Democracy, tasked with compiling data on the national landscape of democracy centers at institutions of higher education. I began to reflect on the idea of democracy, particularly what democracy means for different people and how communities of different experiences and perspectives engage with democracy. This matched exactly what I did every day as a chorus teacher – it was my responsibility to facilitate dialogue and engagement among all of the students, ensuring that each student contributed their voice to our collective mission.

When conducting an ensemble, there are layers of interpretation – there’s the interpretation I create myself, the interpretation the collective ensemble creates, and the interpretation that individuals bring based on their own life. The beauty of the music experience comes from negotiating those interpretations so that our performance represents what we want to communicate both as individuals and as a collective. That is what democracy is, the negotiating between individual and collective identities to ensure authentic representation.

So what prompted you to leave teaching and join Arts for Learning?

I’ve begun to think more broadly about arts engagement. While I loved teaching and loved the students, I would like to utilize my ideas and my experiences to help foster collaboration between organizations and communities to ensure that everyone has an opportunity to contribute their voice and reflect on their perspectives and the perspectives of others through high-quality arts engagement.

As I’ve been investigating the social sphere and the social role of the arts, it’s clear that students are sometimes not presented opportunities in an equal way. And so, it’s up to organizations – like Arts for Learning – to fill those gaps for disadvantaged and marginalized communities where the arts are a powerful means of helping students achieve but also to feel represented and to represent themselves.

What are your goals with Arts for Learning?

In working with the existing artists on our roster, in recruiting new artists, and in developing programming, I want to make sure Arts for Learning is engaging students in ways that are appropriate for 21st century learners. The experiences we offer students should be 21st century experiences—so thinking about what is relevant to our students today, what is relevant about technology in terms of the way we consume the arts, and what are the relevant values we-as-a-society want to promote.

If you’re thinking about only using music and musical experiences to prepare kids to sit quietly at the symphony, that’s doing a disservice to the power of the arts today and the ways that the arts can connect, educate, and inspire today’s young students. Students are willing to be engaged and willing to create, but they want experiences that authentically engage and authentically reflect them.

(An active member of the community, Drew sings in the Virginia Chorale and works as the staff bass at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church and at Ohef Sholom Temple. Drew lives with his partner, Kevin, in Norfolk.)

I’ve got to ask – you grew up in Syracuse, went to college in New Jersey, and then lived in Germany – why settle in Virginia?

Well, in the fifth grade I had to do a presentation on Thomas Jefferson. Through my research for that project, I developed this idyllic, picturesque idea of Virginia, this view of rolling hills and Colonial Williamsburg and Monticello, and so I’ve just had this fascination since then. I feel a lot of pride when I tell people I live in Virginia. It feels like an accomplishment of mine, which seems kind of silly, but I love it. In three hours, I can be in D.C., in two hours I can be at Jefferson’s Monticello, in twenty minutes I can be at the beach, and every day I hear the fighter jets and see the aircraft carriers – what’s not love? I feel like I’ve come home.